Hi everyone, thanks for joining me for Blister Prevention Office Hours this month. It’s Rebecca Rushton here. Today, we’re going to talk about the four things we can learn about foot blisters from massage. We’re going to look at a few technical things, but I’m going to make this really not overly technical, because I’m not really that good at physics myself and I get lost in all of that talk. But my aim is to make this meaningful and accurate, but really easy to understand. So we’re going to have a look at things like shear, rubbing, friction, coefficient of friction. Plus four takeaways from this presentation, and the one big difference between massage and foot blisters, that is really important.

Shear

So, first of all, where is shear in this picture? Is it in front of the thumbs, under the thumbs or behind the thumbs? If the masseuse was literally just pushing straight down, there would be no shear. All there would be is compression under the thumbs. But as soon as the thumbs start to move in one direction, let’s say they move upwards, then there will be shear deformation within the skin and the soft tissues under the thumbs and just back from the thumbs. The point I’m trying to make here is that this puckering of skin at the top, that’s not the important part, that’s not where shear is. It’s under and a little bit behind the thumbs.

Rubbing

Next rubbing – a very benign term that on the surface of it doesn’t need any explanation. But in fact, it does. Because every single rub action can be divided into two separate parts. The first part where there’s no relative motion. And the second part where there is relative motion. When we think about rubbing, I dare say, most of us just think about the part where there is relative motion. And we forget about the first part. But you’re going to see in a moment that it’s probably the first part that’s the most important when we’re talking about the magnitude of shear deformation. What would be really helpful is, instead of there just being the one word that describes both of these in combination, which is rubbing, is if we had a term that described the first part, and another term to describe the second part. Ideally these words would already be in most people’s vocabulary, so it would be easy to explain blisters and shear a lot more easily to our patients. The fact is, there are no such words. All we have is rubbing which is applied to the second part of the rubbing action – where there is relative motion, and nothing for the first part – where there has been deformation of the soft tissues, but no relative motion yet.

Massage without oil

So we’re going to have a look at this with the example of massage. Firstly, with no oil, as the masseuse presses down and starts to move their thumbs forward, the thumbs get stuck on the skin. It’s hard to move them relative to the skin and the motion of the thumbs is confined to “give” in the soft tissues. So there’s no relative motion between the skin of the thumbs and the skin of the person’s back, but there is some sort of movement within the soft tissues under the skin. The degree of movement is determined by the “give” in the soft tissues, and that’s exactly what shear deformation is. So shear magnitudes are quite large in this situation, particularly if we are pressing down and forward hard, trying to get the thumbs to move. To get relative motion between the thumbs and the patient’s back, we have to either reduce pressure or we have to make it more slippery. That means reducing the coefficient of friction.

Massage with oil

If we compare that to when there is oil added to the equation, obviously, the thumbs slide very easily due to the reduced coefficient of friction. We’ve made it more slippery between that interface of the thumbs and the skin of the patient’s back. Even if you press really hard, you’ll get a lot of compression, but you won’t get a lot of shear. So, in this case, reducing the coefficient of friction, making it more slippery, which creates more rubbing and less shear.

Just let that sink in for a moment. So, rubbing is the answer here to less shear.

Friction

Let’s quickly look at friction. Friction is basically the force that resists the movement of the thumbs over this person’s back. There’s a movement force from the thumbs moving forward. Friction is working to oppose that motion. So it is working in the opposite direction. And it’s defined by the coefficient of friction times the normal force. So the lower the coefficient of friction (the more slippery it is), the lower the friction force. And similarly, the lower the pressure (or the normal force) the less hard you press, the lower the friction force.

What we’re looking at here is this part of the Blister Prevention Mechanisms chart. Friction force: that’s the force that resists the movement of the thumbs over the person’s back. It is determined by how slippery or grippy it is, and how lightly (or firmly) you press.

Takeaway 1:

Every single rub action can be divided into two separate parts. The part where there’s no relative motion and the part where there is relative motion. We often ignore the first part. And I’m going to show you in a moment, the part where there is no relative motion, determines the magnitude of shear deformation. So in fact it’s actually very important when we’re talking about shear and shear-related damage.

Takeaway 2:

Shear deformation magnitudes can be reduced by either reducing pressure, or reducing the coefficient of friction. Pressing less hard, your thumbs will find it easier to move and there’ll be less shear. Similarly, make it more slippery and your thumbs will move much easier, and there will be less shear (a lower shear magnitude). Rubbing is often the solution to reducing the magnitude of shear deformation, rather than the problem. Another one just to sit on for a moment. Rubbing is often the solution. Yet, so many of us and basically all of our patients think that rubbing is the enemy – rubbing is what causes blisters. It’s not!

Coefficient of friction

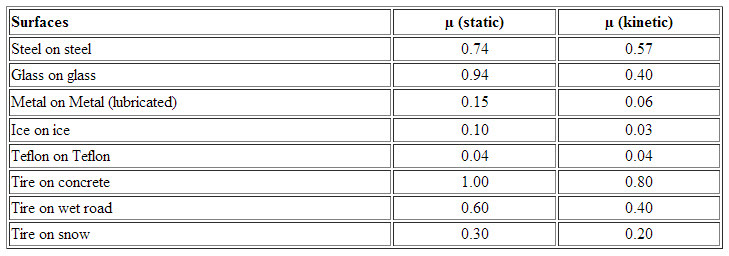

What else can we learn? Let’s have a quick look at coefficient of friction. There are two measurements of coefficient of friction. There’s the static and the dynamic (often referred to as kinetic or sliding coefficient of friction). So, here’s a graph. You can see the first part of the red line going up at an angle. This is the period where there is static friction. This is the first part of the rub – there’s no relative motion between the thumbs and the patient’s back.

The next bit is the part where there is relative motion. Look how the kinetic coefficient of friction is lower than the static coefficient of friction peak. So this is the motion. This is where the thumbs are still stuck on the person’s back and have not moved yet, and this is where they’ve moved. Isn’t that interesting?

So, we think about rubbing as this part (dynamic friction). But if we’re thinking about shear-related skin trauma, we should be thinking about static friction. Because peak coefficient of friction is within the static coefficient of friction range.

Every pair of surfaces has a particular coefficient of friction and you’ll see in the table at the bottom there are different pairs of materials, and you’ll see in every occasion (except for teflon on teflon), the static coefficient of friction is higher than the kinetic coefficient of friction.

Takeaway 3:

The magnitude of shear is determined by peak static coefficient of friction. So the longer the two surfaces are stuck together, the larger the shear deformation. Rubbing shouldn’t necessarily be seen as the problem.

Takeaway 4:

The fourth takeaway is, dynamic or sliding coefficient of friction is (almost) always lower than the static coefficient of friction. Encouraging relative motion (rubbing) is how many blister preventions work? That’s how lubricants work. Obviously we can make a direct comparison here. It’s how Engo patches work – not at the skin-sock interface but at the sock-shoe interface. It’s how moisture management strategies work. These strategies are aiming for a drier environment. And we know when things are drier, they have a lower coefficient of friction. So you might not have really made the connection, but moisture management strategies are actually trying to encourage movement somewhere, earlier. That’s how they work. So, rubbing is often the solution. Not the problem. But it’s hard to get this across to our patients.

Recap

Just to recap, what we’ve looked at here is Friction Force. We’ve looked at the force that resists the movement of the thumbs of the masseuse, over the patient’s back, and it’s determined by how slippery it is, and how hard they press. Particularly, if you reduce the coefficient of friction, you’ll be reducing friction force and reducing the magnitude of the shear deformation in the soft tissue.

Bonus Point

Here’s our bonus point. This is a very important point to make. In massage, the skin is being moved over the stationary bones (ribs, vertebrae). But in blisters, the bones (eg: met head, posterior calcaneus) are moving over the stationary skin. So, when we look at the blister situation, everything external to the skin (the sock, the shoe and the ground), all of these things are in stationary contact (this is a prerequisite for efficient gait). But the bones are moving back and forth within the foot. That’s the thing that creates the shear. In opposition to massage, where the patient and the bones of the patient are stationary. But there’s an external force that is trying to move the skin relative to those stationary bones. Can you see the difference there?

So we can’t really draw a direct comparison between massage and foot blisters because, in the massage situation, the things that are external to the patient’s skin (thumbs) they are the things that are moving. Whereas in blisters, it’s the patient’s bones themselves that are moving. This is an important difference to recognize.

If we look at this picture, the skin surface is in exactly the same position here in all three pictures. It’s the bone that’s moving. So as soon as the bone starts to move one way, the force of friction is opposing that movement. And then the other way. And of course, the friction force doesn’t move anything – it’s just opposing the movement force of the thumbs.

The relevance to foot blisters

So that’s enough talk about massage, let’s get back to foot blisters. While we look at these pictures, let’s just read these takeaways again.

- Every single rub action can be divided into two separate parts. The part where there is no relative motion; and the part where there is relative motion. We often ignore the first part. We often blame everything on rubbing. And look, there may be relative motion. But it’s actually the part where there is no relative motion that determines how large the shear deformations are in the skin.

- Shear deformation magnitudes can be reduced by reducing pressure and reducing coefficient of friction. So in either situation, we’re encouraging relative motion. Therefore, rubbing is often the solution rather than the problem. That’s what we’re trying to do when we reduce pressure. We’re actually trying to allow some movement at an interface, sooner. And that relieves the shear deformation magnitudes so that they are actually lower.

- The magnitude of shear is determined by the peak static coefficient of friction. The longer the two surfaces are stuck together, the larger the shear deformation. And so rubbing shouldn’t necessarily be seen as the problem.

- Dynamic coefficient friction is lower than static coefficient of friction. Encouraging relative motion is a legitimate blister prevention strategy, just like those strategies I named earlier. So, rubbing is often the solution.

When we are attempting to get relative movement sooner, we’re encouraging rubbing. If this black line was comparable to the first graphs that we saw earlier, when we are trying to encourage rubbing, we’ve got the same movement force, but because it’s slippery, we get relative motion sooner. The coefficient of friction has peaked at a lower point which means that the shear deformation magnitude has peaked at an earlier point. So this is essentially what we’re trying to do with, let’s say lubricants – we’re trying to encourage earlier relative motion. So instead of it happening here, it’s happening here, and therefore shear has peaked at a lower point.

Conclusion

So I hope that is helpful. It’s a bit more involved than you might think. And is it any wonder that our patients aren’t really grasping what causes blisters in a more thorough sense, because it’s really hard to describe. If I have a patient in the chair, I place my fingertip on the top of their foot and say: Most people think this is what causes blisters (demonstrate rubbing) but it’s actually this (demonstrate shear). There’s actually no movement between the skin of my fingertip and the skin of the back of my hand. And yet, we can see there’s all that “give” in the soft tissue, that’s the stretching and distortion of the soft tissues. If that happens for long enough and to a large enough magnitude, there’ll be a mechanical fatigue within the skin, which is basically a little tear under the skin surface, and that’s the initiation of the blister injury. So yeah, that’s how I describe things.

Q & A

So let’s get into Question Time. We just had the one question this week. Maryann asks “I recently had three blisters on the planter pad. I didn’t deroof the blisters but they ended up getting larger and more painful each day that I had to release the fluid and deflect and dress. Is it a better idea to open blisters on the plantar surface of the toes?”

I often do lance blisters in race situations where I’m there and people can come and see me for redressings and stuff like that. But it’s not always advisable. So if you’re asking me, then yes, I often will. But I always have a conversation with the patient or the runner or whoever it is and we talk about the fact that we’re opening the blister up to infection and is that worth doing? So we have to have a chat about any elevated risk for infection. They’re going to need to have the right gear, and enough of it to perform multiple redressings. So they need antiseptic and a Band-Aid at the very least. And they need to know that it’s not a ‘do it once and it’s done’ in one episode kind of job. We’ve opened up that blister. Now it needs to be redressed until that heals. So these are the things I go through.

I’ll often be influenced, of course, by the patient’s activity level, so if it’s mid-race or it’s the end of the race and it really depends what shoes they’re wearing, potentially what their activity level is going to be. So if they’ve just finished a race and they’ve got the weekend off, we might be more inclined to leave it and let the blister fluid resolve of its own accord. But look, it’s such an involved topic. And in fact, we had an Office Hours last month exactly on this topic about whether to deroof, lance or leave blisters alone. It took an hour and we looked at a whole bunch of scenarios with blister pictures. So I recommend that you go to have a look at that, Maryann. You’ll find it on our Office Hours page here. We went through the whole shebang so yeah, I hope that one helps Maryann. But good question and basically, yes, if it’s me I generally do. But it’s not appropriate in all situations.

So guys, that’s it for this month. If you have any questions, if you want to watch the replay, it’s always going to be on the Office Hours page on our pro site. I’ll be back next month, the first Wednesday of the month and we’ll talk blisters again. Thanks for joining. Bye for now.